Humanizing Coronavirus Care

PPE Portrait Project in use at Stanford, UMASS

Mary Beth Heffernan

PPE Portrait Project

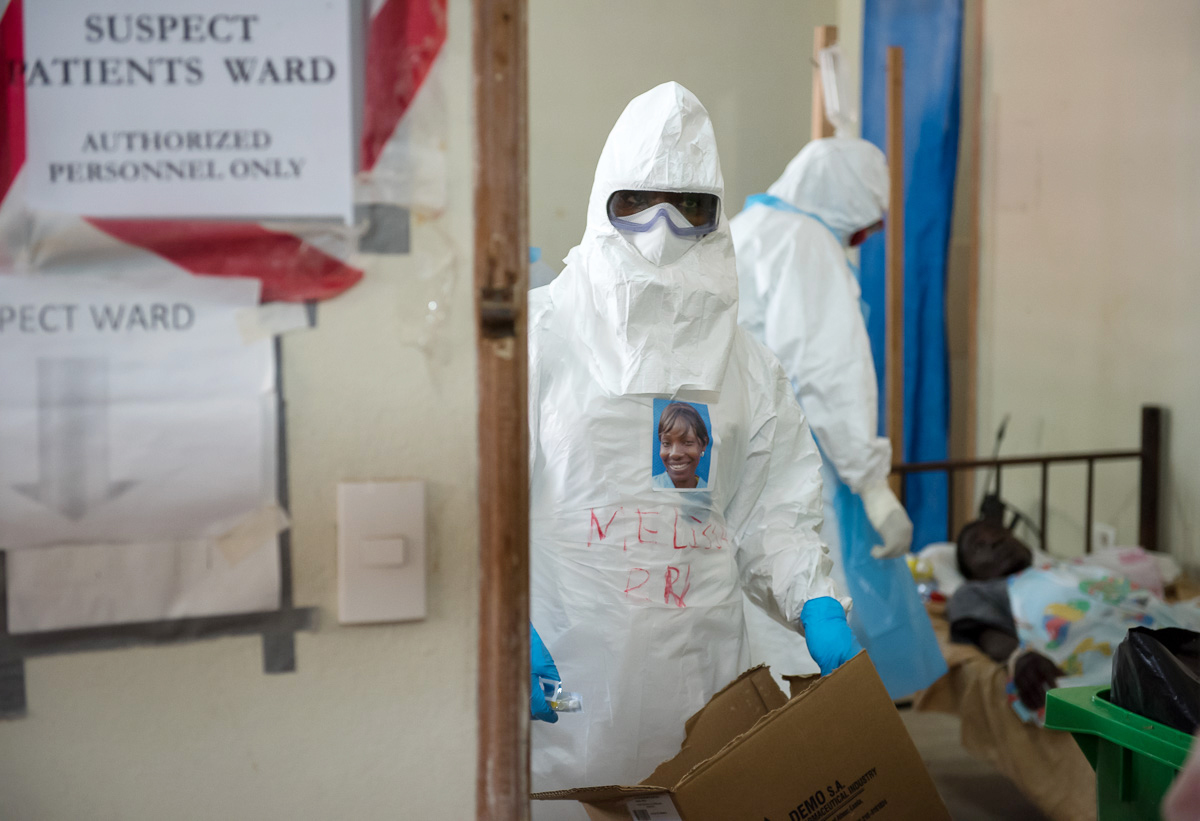

“The patients arrive, at first fearful of the people in spacesuits whose faces they cannot see.” Daniel Berehulak. NY Times, October 31, 2014

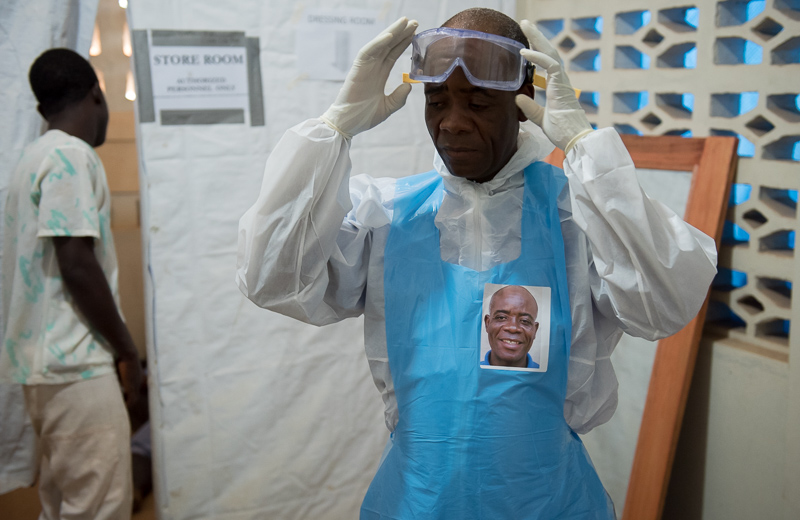

The PPE Portrait Project is an art intervention designed to improve Ebola care. Inspired by Joseph Beuys’ notion of “social sculpture,” I seek to ameliorate the alienating appearance of the Ebola “hazmat” suits with headshot portraits of the health care workers inside. It’s important to me that the portrait labels have tangible medical and psychosocial benefits.

The headshot portrait labels are designed to reduce suffering and improve health outcomes in EVD care. The “otherworldly” appearance of the personal protective equipment (PPE) contributes to patients’ isolation and fear of Ebola virus disease (EVD), while its frightening effects diminishes clinicians’ ability to establish trust and emotionally connect with patients. A headshot printed on disposable adhesive labels and affixed to the upper chest area of the outer protective gear enables a patient to see (a photographic image of) their healthcare worker’s face. The practice also helps improve receptivity towards ambulance technicians and burial teams entering sensitive communities.

Where were the PPE Portraits in use?

PPE Portraits were used in Liberia at the ELWA II Ebola Treatment Unit in Monrovia and the IOM Tubmanburg ETU in Bomi County. IOM Tubmanburg ETU effectively beta tested the project, with patients reporting, “I like that I can see who is taking care of me.” Another patient said “It is nice I can see what you look like behind that [PPE].” One of our nurse assistants said she thought the pictures were a “the best idea” because the patients, when they are discharged, have no idea who took care of them and “this way they know who helped them.” All the staff agreed that the PPE looked much less scary with a grinning picture on the front and have noted that, when in the Red Zone, the staff also look at the pictures. One doctor said that “the PPE makes everything so impersonal, it is nice to look around and be like, ‘Oh that is Bomia, or oh that is Gorpu.’ It makes it feel more like I am working with people, with my team, instead of inanimate objects.”

Isolation, distress, and the positive effects of social exchange

Source isolation can be an extremely distressing and frightening experience1 even for periods as short as 24 hours[1]. The fear experienced by EVD patients is likely multifold: fear of the deadly disease itself,[2] and the frightening appearance of PPE.[3] Social isolation and psychological distress have been shown to have detrimental effects on health and illness recovery.[4] Conversely, positive social exchanges substantially improve immune system response to disease. [5] HCPs agree that PPE design should be less frightening to patients.7 Wearable headshots can lessen the frightening appearance of PPE by personalizing the HCP-patient encounter, thereby reduce patient stress. Furthermore, the wearable photos provide a modicum of social bond, enhancing the patient’s ability to benefit from positive social encounter boosts in health outcomes. 8

What gave rise to the PPE Portrait Project?

When the Ebola crises exploded on the ground and in the press in late summer and early fall of 2014, my immediate response was that photography had a role in mitigating the suffering caused by the terrifying appearance of health care workers clad in personal protective equipment. My question was embarrassingly simple: “Why don’t they put portrait photos on the outside of the PPE?” Given my long interest in the intersection of the body, photography and illness, I realized that I was positioned to make a small photographic intervention that could have outsized psychosocial, and even medical, benefits.

Biography

I earned my MFA in photography at the California Institute of the Arts, mentored in the history of physiognomy in photography by the distinguished photographer and historian, Allan Sekula. A fellow at the Whitney Museum of Art Independent Study Program, I studied and made art through the lens of critical theories of representation, race, and gender. My courses are informed by critical histories of the instrumental uses of photography vis-a-vis bodies, including medical, scientific, criminology, and popular images. My artwork often uses the visual rhetoric of medical and scientific imaging against the grain to grapple with how we emerge as individuals in the cross hairs of these powerful institutions. The interplay of corporeality and its representation is an ongoing animating theme in my work.

The PPE Portrait Project is made possible by generous support from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation for humanities in medicine, and grants from Occidental College.

1 Gammon, J. The psychological consequences of source isolation: a review of the literature. J. Clinic Nurs. 1999; 8:13-12.

2 Knowles H (1993) The experience of infectious patients in isolation. Nursing Times. 89,30, 53-56.

3 Gould D. (1987) Infection and Patient Care. William Heinmann Medical Books, London.

4 Broeder JL (1985) School-age children’s perceptions of isolation, after hospital discharge. American Journal of Maternal and Child Nursing. 14, 3, 153-174.

[4] Karelina K, DeVries, AC (2011) Modeling Social Influences on Human Health. Psychosom Med. January; 73(1): 67-74.

- Karelina et al. p.

7 Baig AS, Knapp C, Eagan, AE, Radonovich, LJ (2010) Health care worker’s views about respirator use and features that should be included in the next generation of respirators. American Journal of Infection Control, 38, 18-25.

8 Baig, et al. p.5.